“The music sector in Africa’s audiovisual sector needs to be revalued

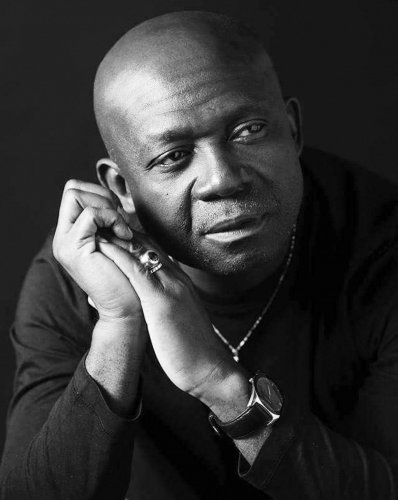

The copyright expert, who is also president of the Pan-African Alliance of Music Authors and Composers and an executive member of the International Music Council, talks about the importance of understanding the importance of musical works in the audiovisual sector, particularly in cinema. We met him in February 2019 in Ouagadougou, at the Pan-African Film and Television Festival of Ouagadougou.

You are a well-known artist in music circles. What justifies your presence here in Ouagadougou, at a festival dedicated to cinema?

We have come to lead an international conference on copyright in the audiovisual field. People do not know that in the audiovisual field, sound is involved. This does not necessarily refer to the sound effects you hear in films, but it is music. We wanted to establish the correlation between music and audiovisuals, starting from the question of whether the images would be more expressive and could give more emotion if they were not accompanied by music. It seems to me that they would not. In the production chain of cinematographic works, there is the author of the musical compositions and all those involved are formally bound by contracts. The producer signs contracts with the actors, with the scriptwriter, with the author of the musical works and, for broadcasting, all these people need authorisations, and this is where copyright comes in, since the creation of an audiovisual work falls under copyright.

Music was already present in the cinema before voices, in the era of silent films. What is the chain of creation of musical works for the cinema?

There are many different professions in the audiovisual and musical fields. You have the sound technicians, the scriptwriters, the directors. But, to focus on the musical field, you said something very important, which is the mention of silent cinema. This is not true in absolute terms today. People think that when we talk about audiovisuals, there is only the image. Music is too often forgotten. This is why people ask me what I do in Ouagadougou, at Fespaco. Music is not very important in the African film context. When you see that music films have made international successes like Ennio Moricone (The Good, the Bad and the Ugly), Whitney Houston (Bodyguard), Céline Dion (Titanic), you measure the impact of music on film productions. Without these songs, these films might not have been so successful. But the music is always a small part of the film. And we are fighting for it to find its place in the audiovisual field.

The music sector in the audiovisual sector in Africa must be revalued. Let me give you an example. Do you know that, in general, everyone is rewarded, except the author of musical and audiovisual compositions? Yet the latter is part of the audiovisual ecosystem. For film music, contracts must be signed with publishers, with artists, with songwriters.

Music is present everywhere, whether in fiction, documentaries, cartoons, etc. Music must be given the place it deserves. And even when we look at the awards, we realise that directors, scriptwriters and actors are rewarded, but rarely the songwriters.

Is there an awareness for a better consideration of music in the audiovisual sector?

That is why the International Confederation of Societies of Authors and Composers (Cisac) came to Fespaco and organised this international conference. And I, as president of the Pan-African Alliance of Music Authors and Composers and a member of the International Council of Music Authors, have drawn attention to this aspect of Fespaco, which has also responded favourably. The Cisac has just signed a historic partnership with Fespaco.

In the long term, we must really make institutions aware of the role of music in the audiovisual sector. Sometimes it is not bad faith on their part. There is a huge need for communication that we must fill. We need to show them the ins and outs of this correlation. They need to understand each other’s rights and obligations. The world is changing. We have to anticipate a number of things.

What are the different types of contracts that can link a songwriter to a film project?

There are different types of contracts in the audiovisual field: the production contract, commissioned works, etc. It is good to have a contract with a composer. It is good to have a marriage between music and audiovisuals. But all these players have rights and everything must be formalised beforehand, otherwise it doesn’t work. In the Anglo-Saxon system, it is different. The executive producer has all the powers because he has money. In our Latin system, the director is the all-powerful one. It depends on the system. But, again, it is important to know all the prerequisites.

Practical case: there is a film project that is entitled to the music section?

Actually, there are two cases. If the work is pre-existing, you have to ask the production company, the author, the collective management society if he is affiliated to it, for permission to use it. When you use it, this implies that the rights have been assigned to you and, in return, you must pay them royalties once the film is broadcast. If this work is made by a different producer, then the producer will sign a contract with the performer – the one who performs the works in the film. The performer will receive neighbouring rights, and the phonogram producer will also receive rights.

The second case is that it may be a commissioned work. The parties involved can sign a commissioning contract. You go to the songwriter, explain the project to him and he composes music especially for your project. In this case, the songwriter signs a contract with the producer. In the Anglo-Saxon context, once the songwriter has finished, the producer does not owe him anything. In the French-speaking system, the songwriter can reserve certain rights if you agree that you will produce the music, but not in the context of a commissioned work. The songwriter can do his or her job and ask for rights every time the film is broadcast.

0 Comments